Be Well.

David

Drought of 2012 conjures up Dust Bowl memories, raises questions for tomorrow

September 15, 2012 -- Updated 1653 GMT (0053 HKT)

A farmer and sons walk in the face of a dust storm in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, in April 1936.

(CNN) --

Some 3.5 million people fled their homes in Oklahoma, Texas, and

elsewhere, the bone-dry landscape, blistering heat and choking dust

storms unfit for growing and raising the crops and cattle they relied on

to survive.

Thousands

more, many of them children and seniors, could not escape, killed by an

infection dubbed "dust pneumonia" and other illnesses tied not just to

the extreme weather and poor living conditions but to massive,

fast-moving dust clouds.

Those clouds and barren terrain across much of middle America gave this period of despair its name: the Dust Bowl.

There were suicides,

there were bankruptcies, there were people scrapping for whatever they

could find to live. And these were not overnight horror stories: They

were repeated day after day and year after year, at a time when much of

the United States and world was already debilitated by the Great

Depression.

"If

you can imagine what's happening now and multiply it by a factor of

four or five, that's what it was like," said Bill Ganzel, a

Nebraska-based media producer who interviewed survivors of the 1930s'

environmental and economic disaster and penned a book, "Dust Bowl

Descent." "And it lasted for the entire decade."

Nothing

in U.S. history can compare to that calamity of eight decades ago,

including the historic drought now gripping much of the country.

That

doesn't mean, though, there isn't considerable

suffering and devastation now in most of the United States. Or that

dire conditions could well persist for several years, as they did during

the 1930s -- compounding negative impacts of drought, thus ruining even

more livelihoods and lives despite technological and agricultural

advancements of recent years.

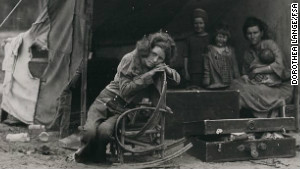

Florence Thompson, right, and her children were featured in Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother" photo.

"Mother

Nature holds all the cards,"

said Mark Svoboda, a climatologist with the National Drought Mitigation

Center. "You roll the dice ... every year. Nothing will make you

quote-unquote drought-proof."

This

year, Hurricane Isaac helped alleviate the current drought in some

locales, but not in most, and certainly nowhere near enough to put a big

dent in a phenomenon that's affected millions.

Is it happening again?

Over

63% of the contiguous United States in early September was suffering

moderate to exceptional drought, nearly twice the land affected a year

ago, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Using July data, the

National Climatic Data Center reported that America is in the midst of

its most expansive drought since December 1956.

The

combination of dry conditions and extreme heat -- including hundreds of

record-breaking temperatures this summer -- has been unbearable for

many. The drought's impact has been seen in ways big and small, from

leaves falling early and lawns turning brown to farmers giving up and

lakes drying up, exposing hundreds of dead fish.

"It

does look like a moonscape," Svoboda said of parts of western Oklahoma,

where dirt drifts into mounds and soil climbs over fence posts. "There

are some parts of the country where (dire farming conditions) have

nothing to do with them failing to till over the soil," as was commonly

blamed for "dust storms" of the 1930s.

Driving

through southern Wisconsin, CNN iReporter Jim Jostad saw heap after

heap of chopped-down corn sacrificed by farmers who had conceded this

year's crop, hoping if anything to salvage some of the loss by selling

off as cattle feed what did sprout up.

Dozens

of farmers markets in Oklahoma were without vendors months

earlier than had been expected because their bounty was so meager, said

Nathan Kirby of the state's Department of Agriculture, a year after

closing even earlier due to similarly hot, arid conditions.

While

consumers may be worried about rising food prices tied to the drought,

many farmers have seen their incomes all but evaporate because crops

won't grow -- finding even irrigated farmlands cannot pump in enough

moisture, given the rate it evaporates back into the atmosphere in high

heat.

It

hasn't been easier for those who raising cattle and other

animals, at a time of scorched pastures and scanty, costly hay and

other feed. Ranchers have been forced to prematurely sell off their

cattle, saying they had no other choice because it cost more to feed

them than to keep them.

Oklahoma

ranchers "liquidated" -- meaning slaughtered or sold off, without

replacing them with newborns or new purchases -- 14% of their livestock

last year, said Derrell Peel, an Oklahoma State University faculty

member who works with ranchers and affiliated companies in that state.

The only reason rates haven't been similarly high after this summer is

because ranchers don't have as many animals to sell, he said.

The nation's severe drought has been especially hard on cattlemen like Colorado rancher Gary Wollert.

Families

trying to make a living raising cattle have been especially hard

pressed. Take Mark Argall of Mountain Grove, Missouri, who sold 33 of

his cherished cows (leaving only a few behind) for less than half what

they might have earned before the drought.

"They're

not just numbers on a computer," Argall said. "They're members of the family."

Can it happen again?

So what can be done to prevent another Dust Bowl disaster?

Rains

from Hurricane Isaac might have made

headlines, but they alone won't make a dent in the drought. Ironically,

the Dust Bowl era had wet spells, too -- including flash floods in the

Great Plains -- though they did not alter the devastating equation much,

according to U.S. Department of Agriculture meteorologist Brad Rippey.

What

farmers and ranchers do have working in their favor, compared to the

1930s, are new tools, techniques and other developments that help them

better manage droughts, storms and other harsh weather realities.

Svoboda,

with the National Drought Mitigation Center, rattles off several such

changes -- from more effective soil preservation measures to hybrid

seeds to the inception of center pivot irrigation. He adds, too, that

things like cell phones and computers make it easier for farmers,

ranchers and others to understand what's coming, then adjust.

And

the most significant difference between the 1930s and today -- and the

main reason for hope that it won't be as bad -- is time. The Dust Bowl

era is generally defined as an eight-year stretch; while parts of

Oklahoma and Texas are in the second year of drought, the rest of the

United States is in its first.

In other words, there's still a long way to go.

If the precipitation picks up, "row farmers" cultivating crops like corn, soy beans and sorghum

using modern farming practices should be able to recover next year.

"If

they have a normal rain pattern, it's basically a zero recovery

period," said Rippey. "You are going from a (devastated) 2012 crop to

normal."

But

those raising livestock may feel the effects of this drought for

longer, even if there's more rain. Some strained pastureland and hay

fields may revive with above average, more sustained rainfalls than

ordinary. But other lands may be a lost cause, with replanting the only

way to save them. Peel called the next one to two months "critical,"

as some rain soon may help save these lands so ranchers do not have to

start from scratch.

Still,

even if their pastures improve or hay prices drop, those who sold off

many of their livestock in recent years likely cannot afford to buy the

same number back, and return to normal, anytime soon.

"Grazing

and ranching are totally at the mercy of rain-fed crops and pastures,"

said Svoboda, pointing especially to the susceptibility of grass and hay

to a lack of moisture and excess of heat. "They just don't control

those factors at all."

If

drought conditions do persist, they can have a steamroller effect. "The

suns' rays are more efficient (when) you have parched soils," said

Rippey, the USDA meteorologist, adding that it becomes harder for new

moisture to make an immediate impact.

"These droughts, when they tend to go multiple years, it really starts to feed on itself," adds Svoboda.

We haven't got there quite yet, but we could be if more precipitation doesn't fall over the Great Plains and beyond.

As

they try to predict the drought's future, meteorologists say they will

look first to whether this fall and winter are

wetter and cooler than last year, hoping that it will saturate soils

and rivers and spur a wetter trend that continues into next spring and

summer.

As

is, some states out west had two straight La Nina winters that "tend to

really suck you dry," Svoboda explained. Typically lasting a year or

two, La Nina is characterized by cooler than normal sea-surface

temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean that has a domino

effect on global weather -- leading to more rainfall than normal in some

locales and drought in others.

"If

we had a third

consecutive La Nina, there are some statistics that would be scary," he

added. "But the odds of La Nina (continuing) are very small right now."

Still,

no one predicted practically a full decade of minimal rain, maximum

heat during the Dust Bowl era either. The fact is, for all the forecasts

and farming innovations, keeping one's fingers crossed for change in

the weather may be as useful as anything else.

"Right now, it's just a question of Mother Nature giving us a break," said Derrell Peel, from Oklahoma State.

No comments:

Post a Comment