Dear Friends,

http://crowlspace.com/?p=1524

Be Well.

David

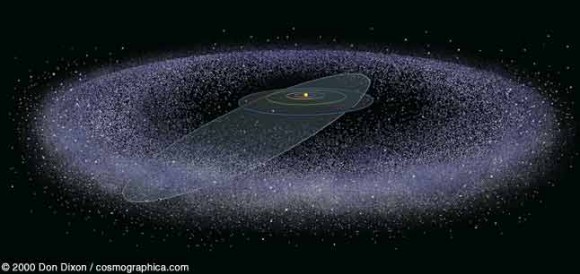

The Unknown Solar System

Just beyond Neptune is the Kuiper Belt, a torus of comet-like

objects, which includes a few dwarf-planets like the Pluto-Charon

dual-planet system. Despite being lumped together under one monicker,

the Belt is composed of several different families of objects, which

have quite different orbital properties. Some are locked in place by the

gravity of the big planets, mostly Neptune, while others are destined

to head in towards the Sun, while some show signs of being scattered

into the vastness beyond. Patryk Lykawka is a one researcher who has

puzzled over this dark, lonely region, and has tried to model exactly

how it has become the way it is today. Over the last two decades there

has been a slow revolution in our understanding of how the Big Planets,

the Gas Giants, formed. They almost certainly did not begin life in

their present orbits – instead they migrated outwards from a formation

region closer to the Sun. To do so millions of planetoids on near-misses

with the Gas Giants tugged them gently outwards over millions of years.

We know what happened to the Gas Giants, but what of the planetoids? A

fraction today form the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud beyond it (how

many Plutos exist out there?) But a mystery remains, which Lykawka convincingly solves

in his latest monograph via an additional “Super-Planetoid”, a planet

between 0.3-0.7 Earth masses, now orbiting somewhere just beyond the

Belt.

Such an object would be a sample of the objects that formed the Gas

Giants, a so-called “Planetary Embryo”. Based on the ice and silicate

mix present in the moons of the Gas Giants, the object would probably be

half ice, half silicates/metals, like a giant version of Ganymede.

However such an object would also have gained a significant atmosphere,

unlike smaller bodies, and being cast so far from the Sun, it would have

retained it even if it was composed of the primordial hydrogen/helium

mix of the Gas Giants themselves. This has two potentially very

interesting consequences. David Stephenson, in 1998, speculated on interstellar planets

with thick hydrogen atmospheres able to keep a liquid-water ocean warm

from geophysical heat-sources alone. Work by Eric Gaidos and Raymond

Pierrehumbert suggests hydrogen greenhouse planets

are a viable option in any system once past about ~2.0 AU. A

precondition that obtains for Lykawka’s hypothetical Super

Trans-Neptunian Object.

So instead of a giant Ganymede the object is more like Kainui,

from Hal Clement’s last novel, “Noise”. Kainui is a “hot Ganymede”, a

water planet with sufficiently low gravity that the global ocean hasn’t

been compressed into Ice VII in its very depths. Kainui’s ocean is in a

continual state of violent agitation, lethal to humans without special

noise-proof suits, but Lykawka’s Super-TNO would probably be wet beneath

its dense atmosphere, warmed by a trickle of heat from its core and the

distant Sun.

Gravitational perturbation studies of planetary orbits by Lorenzo Iorio constrain the orbital distance

of such a body to roughly where Lykawka suggests it should be. A

Mars-mass object (0.1 Earth-masses) would exist between 150-250 AU,

while a 0.7 Earth-mass body would be between 250-450 AU. If we place it

at ~300 AU, then its equilibrium temperature, based on sunlight alone,

would be somewhere below 16 K. That’s close to the triple-point of

hydrogen (13.84 K @ 0.0704 bar), suggesting a frozen planet would

result. However geophysical heat, from radioactive decay of potassium,

uranium and thorium, could elevate the equilibrium temperature to over

~20.4 K, hydrogen’s boiling point at 1 atm pressure. Thus a thick

hydrogen atmosphere should stay gaseous.

To keep liquid water warm enough (~273 K) at the surface, the surface

pressure will need to be ~1,000 bar, the equivalent of the bottom of

Earth’s oceans. An ammonia-water eutectic mixture would be liquid at

~100 bars and 176 K. With a higher rock fraction and higher radioactive

isotope levels (as seen in comets, for example), liquid water might be

possible at ~300 bars. Such a warm ocean would seem enticingly

accessible since a variety of submarines and ROVs operate in the ocean

at such pressures regularly. While the prospects for life seem dim, the

variety of chemosynthetic life-styles amongst bacteria suggest we

shouldn’t be too hasty about dismissing the possibility.

A primordial atmosphere also invites thoughts of mining the helium

for that rare isotope, helium-3. At 0.3 Earth masses and 1:3 ratio of

ice to rock, such a body has 75% Earth’s radius and just 40% the

gravitational potential at its surface – even less at the top of the

atmosphere. Such a planet would be incredibly straight-forward to mine

and condensing helium-3 out of the mix would be made even easier by the

~30-40 K temperature at the 1 bar pressure level. There’s no simple

relationship between the size of a planet and its spin rate, but

assuming Earth’s early spin rate of 12 hours, then the synchronous

orbital radius is just 2 Earth radii above the operating altitude of a

mining platform. A space-elevator system would be straight-forward to

implement, unlike the Gas Giants or even Earth.

Travelling to 300 AU is a non-trivial task, ten-times the distance to

Neptune. A minimum-energy Hohmann trajectory would take 923 years,

while a parabolic orbit would do the trip in 390 years. Voyager’s 15

km/s interstellar cruise speed would mean a trip of 95 years. A nuclear

saltwater rocket, with an exhaust velocity of 4,725 km/s, could be used

to accelerate to 3,000 km/s, then flip and brake at the destination. The

trip would take six months, which is speedy by comparison.

No comments:

Post a Comment