CYRUS THE GREAT

CYLINDER – LEGACY OF THE ANCIENTS

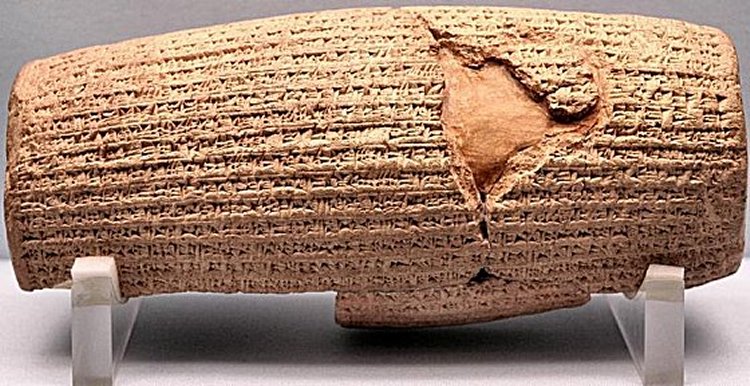

The Cyrus Cylinder,

sometimes referred to as the first “bill of human rights,” traces its origins

to the Persian king Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylon in the sixth century

B.C.

Almost 2,600 years

later, its remarkable legacy continues to shape contemporary political debates,

cultural rhetoric and philosophy.

One of the most celebrated

objects in world history, the Cyrus cylinder is a fragmentary clay cylinder

with an Akkadian inscription of thirty-five lines discovered in a foundation

deposit by A. H. Rassam during his excavations at the site of the Marduk temple

in Babylon in 1879.

In this text, a

clay cylinder now in the British Museum, Cyrus describes how he conquers the

old city. Nabonidus is considered a tyrant with strange religious ideas, which

causes the god Marduk to intervene. That Cyrus thought of himself as chosen by

a supreme god, is confirmed by Second Isaiah; h is claim that he entered the

city without struggle corroborates the same statement in the Chronicle of

Nabonidus.

A second fragment,

containing lines 36-45, was later identified in the Babylonian collection at

Yale University. The total inscription, though incomplete at the end, consists

of forty-five lines, the first three almost entirely broken away.

The text contains

an account of Cyrus’ conquest of Babylon in 539 B.C.E., beginning with a

narrative by the Babylonian god Marduk of the crimes of Nabonidus, the last

Chaldean king (lines 4-8).

Then follows an

account of Marduk’s search for a righteous king, his appointment of Cyrus to

rule all the world, and his causing Babylon to fall without a battle (lines

9-19). Cyrus continues in the first person, giving his titles and genealogy

(lines 20-22) and declaring that he has guaranteed the peace of the country

(lines 22-26), for which he and his son Cambyses have received the blessing of

Marduk (lines 26-30).

He describes his restoration

of the cult, which had been neglected during the reign of Nabonidus, and his

permission to the exiled peoples to return to their homeland (lines 30-36).

Finally, the king records his restoration of the defenses of Babylon (lines

36-43) and reports that in the course of the work he saw an inscription of

Aššurbanipal (lines 43-45).

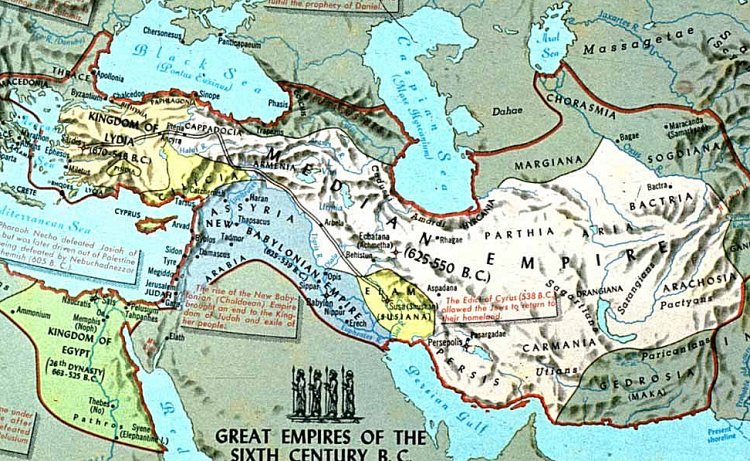

Persian Empire Map

During King Cyrus The Great

The Cylinder—a

football-sized, barrel-shaped clay object covered in Babylonian cuneiform, one

of the earliest written languages—announced Cyrus’ victory and his intention to

allow freedom of worship to communities displaced by the defeated ruler

Nabonidus. At the time, such declarations were not uncommon, but Cyrus’ was

unique in its nature and scope.

When contextualized with other contemporary sources, such as the Bible’s Book of Ezra, it becomes evident that Cyrus allowed displaced Jews to return to Jerusalem.

“One of the goals

of this exhibition is to encourage us to reflect that relations between

Persians and Jews have not always been marked by the discord that disfigures

the political map of the Near East today,” said Julian Raby, The Dame Jillian

Sackler Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art.

“Cyrus was the very

image of a virtuous rule¬—inspiring leaders from Alexander the Great to Thomas

Jefferson—so it is apt that the first time it will be seen in the West is in

Washington, D.C.”

Cyrus – The Great

Of Persia

Under Cyrus (ca.

580–530 B.C.), the Persian Empire became the largest and most diverse the world

had known to that point. Subsequent generations of rulers considered it to be

the ideal example of unified governance across multiple cultures, languages and

vast distances.

Cyrus’ declarations

of tolerance, justice and religious freedom provided inspiration for

generations of philosophers and policymakers, from Ancient Greece to the

Renaissance, and from the Founding Fathers to modern-day Iran, so much so that

a copy now resides in the United Nations’ headquarters in New York.

The message of the

Cylinder and the larger legacy of Cyrus’ leadership have been appropriated and

reinterpreted over millenia, beginning with its creators. The Babylonian scribe

who engraved the Cylinder attributed Cyrus’ victory to the Babylonian god

Marduk, a stroke of what could be considered royal and religious propaganda.

In the fourth

century B.C., the Greek historian Xenophon wrote Cyropaedia, a text that

romanticizes the philosophies and education of Cyrus as the ideal ruler, which

greatly influenced both Alexander the Great and, much later, Thomas Jefferson

in his creation of the Declaration of Independence.

Rediscovered in

1879, the document immediately entered the fray of public debate as invaluable

proof of the historical veracity of events described in biblical scripture. In

the early 20th century, supporters of the creation of the state of Israel

compared the actions of British King George V to those of Cyrus, allowing Jews

to return to Jerusalem.

“The Cyrus Cylinder

and Ancient Persia” includes related objects that highlight some of the

artistic, cultural and historical achievements of the Achaemenid Empire

(550–330 B.C.) of Iran, such as architectural fragments, finely carved seals

and luxury objects from the Oxus Treasure.

No comments:

Post a Comment